Envisioning a Blue Environmental Economy

The waters of Maine are central to life here and have been so for tens of thousands of years. It is a safe bet that these waters will be essential for future generations to thrive here as well.

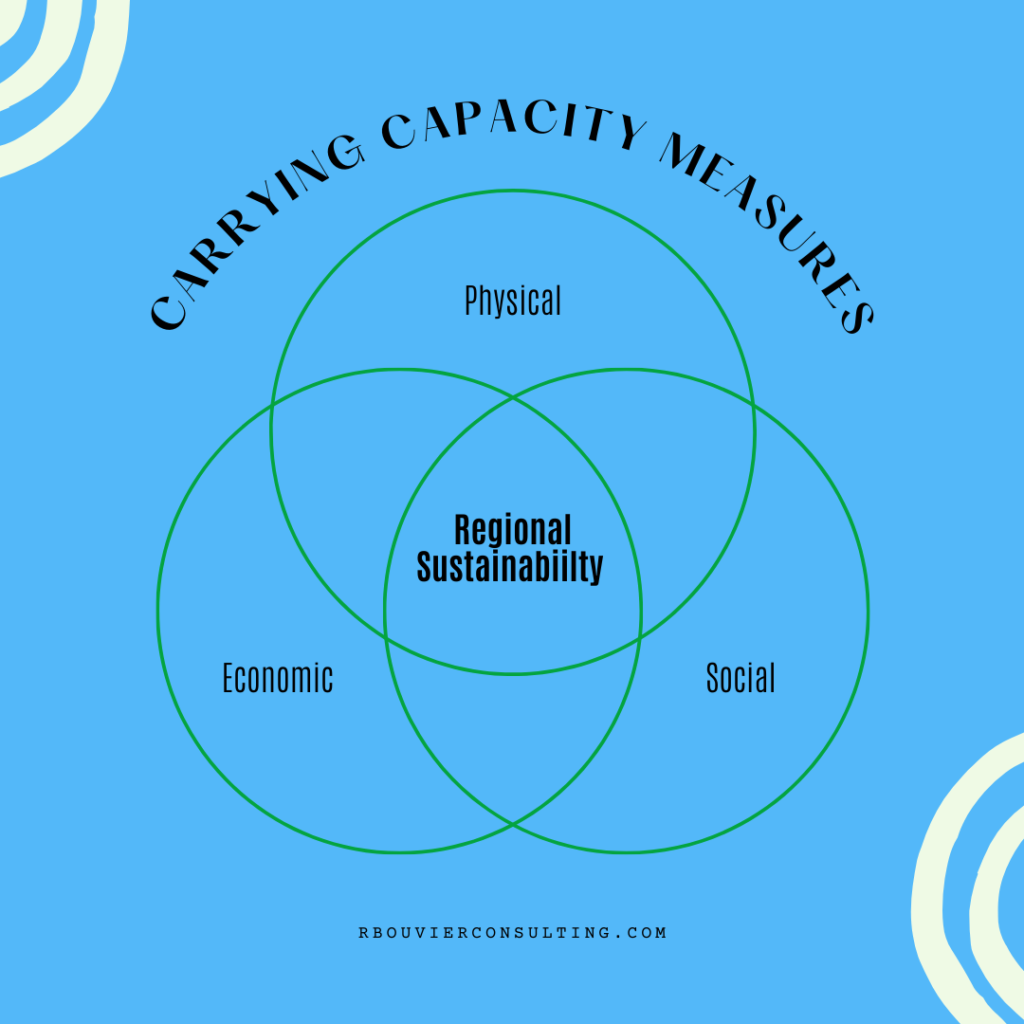

Our mission at rbouvier consulting is to help expand society’s definition of “value” to include all aspects of value, including economic, environmental, and social. Recently, we have been thinking about aquaculture and its economic value. The limiting way that aquaculture is defined misses the wider value of aquaculture to our ecosystem and to future generations.

Limitations of definitions currently guiding policy

The Maine Department of Economic and Community Development and generally every official organization touching aquaculture today are focusing on the value of raising organisms for human consumption. Both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) tout aquaculture’s “efficiency” and its “development to meet demand” for food.[1] [2] Both the Maine Aquaculture Association and the Maine Legislature focus on mariculture only.[3] The Department of Environmental Protection, who are in charge of permitting aquaculture systems, has the most expansive definition:

“Aquaculture is the culture, or husbandry, of marine or freshwater plants or animals. Aquaculture is undertaken in both freshwater and marine systems in a variety of ways, including in: raceways or flow-through systems, ponds, recirculating systems, floating or submersible net pens or cages, and bag, rack, suspended or longline culture.” [4]

We miss some interesting and dynamic environmental applications as well as some of the indirect economic and social benefits if we rely on these definitions. In these well-meaning definitions, we see how they frame value and benefit in a limited way.

For example, in the economic and environmental landscape, there may be more consumers of organisms raised in aquaculture systems than humans, and broader benefit. A recent study out of University of New Hampshire reveals that farmers of cattle are beginning to use seaweed to some nutritional and medicinal benefit.[5]

Another example of limited value estimation is in the production for consumption model itself. Consider Maine’s fish stocking program, which demonstrates how economic benefit goes beyond production solely for human consumption models.[6] The program has economic value that is not measured in terms of consumption of food, but in terms of achieving or maintaining ecological balance. In this aquaculture model, the value is not only in the production of experiences for anglers, measured in the sales of licenses, but also indirectly by the ecosystem services that the fish provide. (Side note: In the case of the inland fishery model, there is no restoration aquaculture to restore habitat for fish to spawn in, which would allow them to regenerate naturally.)

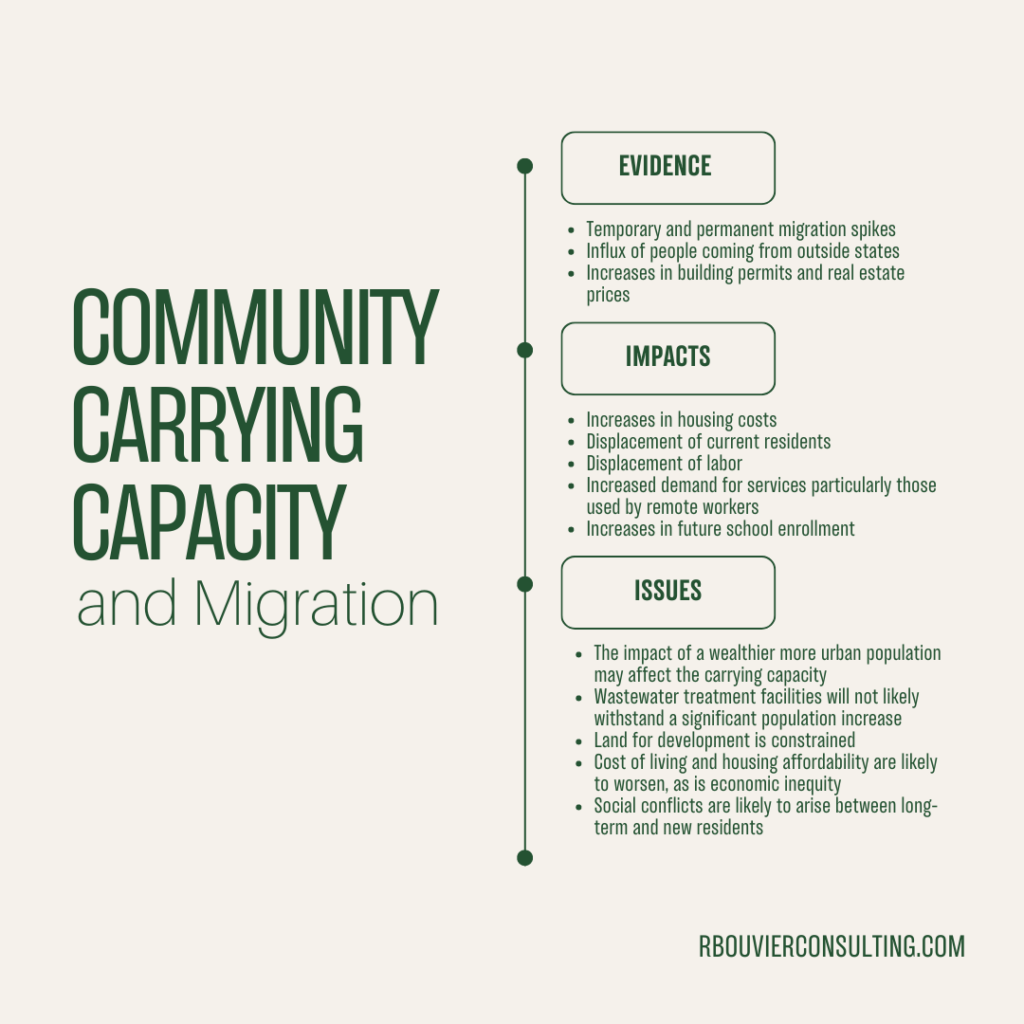

If we continue to design business-as-usual models for aquaculture with a narrow “economic” lens, we may be missing some social or environmental costs, or leaving innovative applications off the table that could reduce costs. Therefore, our working definition of aquaculture includes mariculture (fin fish, shellfish and sea vegetable farms in the ocean), inland hatcheries (fish culture stations), floating islands (for water quality restoration and habitat), eco-machines (aerobic bio digestion of wastewater), and marine permaculture arrays.

Three aquaculture models that warrant a closer look.

Current policy is not supporting three aquaculture models in Maine that present some interesting value propositions for the environment, for the economy and social good.

>Floating Islands

The basic concept of floating islands is mimicry of naturally occurring floating bogs as an intervention in water quality. These aquaculture systems reduce algae, improve dissolved oxygen, and increase habitat.[7] As an aqua-scaping model for restoring biological diversity in surface water and marine areas, floating islands can be aerated, or not, depending on site conditions and design goals. There are several metrics that could be assessed for ecological services from invertebrate populations, to phosphorus parts per million, to water clarity, to temperature and also wildlife habitat creation. The benefits of these systems socially could be measured in property values maintained, and thus tax base stability, or shifts in funding needed to maintain restocking programs. The ecosystem services provided by these islands in dude habitat provision, pollution filtration, and nutrient cycling, among others. In spite of a successful EPA project in Pennsylvania at Lake Lucerne, this aquaculture application is not currently permitted in Maine.[8]

>Eco-Machines

Eco-Machines are another success story that is out of frame with current definitions. These aquaculture systems are living water treatment plants that are also botanical gardens and fin fish farms.[9] There are many examples of these.[10] The model utilizes a series of ecological analogs, and is purported to be less costly than sewer treatment infrastructure and processing. It uses less resources and produces less waste (sludge) than conventional sanitation works, and creates a beautiful community center or educational laboratory. When municipalities and counties are considering high-density development, Eco-machines are a practical solution for wastewater that is not currently being considered.

>Marine Permaculture Arrays

Climate change is warming the oceans which is threatening to seaweed farms and fisheries world-wide. Offshore Marine Permaculture Arrays (MPA) establish kelp forests for the blue economy and for climate adaptation. Dr Brian Von Herzen at the Climate Foundation has pioneered ocean permaculture with the help of the Australian government.[11] His team is cycling cooler, nutrient-rich waters from 500 meters to surface farms, increasing yield of valuable sea vegetables as compared to shore farm production.[12] The current upwell mechanism is the game changer. What they are finding is the regeneration of plankton populations, increases in plant growth, restoration of natural fisheries with increased biodiversity, and aquaculture resilience in the face of tropical storms that devastated shore-zone farms. They have also reversed coral reef bleaching using the wave pump technology.[13] The carbon sequestration benefit of this application is a measurable value. It is an order of magnitude above other approaches to carbon management, such as selling offsets, because 90% of the carbon is in the oceans already, MPAs are transforming it into an embodied form.

These examples make it clear that a relatively small change – expanding our definition of aquaculture to go beyond the production of food for human consumption – can lead to sorely needed innovation and expanding concepts of value. Please contact us if you’d like to know more.

Photo Credits:

“Aquaculture” by NOAA’s National Ocean Service is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

“Floating Bog” by ✿Low✿ is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

“File:Berea College 070308 Ecomachine DB (20062583514).jpg” by IMCBerea College is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

[1] NOAA defines aquaculture as “the breeding, rearing, and harvesting of animals and plants in all types of water environments—is one of the most resource-efficient ways to produce protein.” (https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/aquaculture.html).

[2] USDA defines aquaculture as “the production of aquatic organisms under controlled conditions throughout part or all their lifecycle. Its development can help meet future food needs and ease burdens on natural resources.”(USDA, https://www.usda.gov/topics/farming/aquaculture).

[3] MMA defines aquaculture as “the farming of aquatic species for human consumption and use. Aquaculturists, or aquatic farmers, grow finfish, shellfish, aquatic plants, and other organisms” (https://maineaqua.org/frequently-asked-questions/).

[4] https://www.epa.gov/npdes/aquaculture#:~:text=Aquaculture%20is%20the%20culture%2C%20or,or%20freshwater%20plants%20or%20animals.

[5] In the feed, the sea vegetables apparently relieve gastrointestinal distress in cows. While great for the farms economically due to veterinary costs, there is potential for reduction in methane emissions, a potent greenhouse gas that climate resilience protagonists would love to measure. UNH Today – Maine Farmers Receptive to Seaweed Feed: Survey highlights receptiveness of organic dairy farmers to feeding methane-reducing feeds – April 4 2024 (https://www.unh.edu/unhtoday/2024/04/maine-farmers-receptive-seaweed-feed)

[6] The Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MDIFW) currently operates eight fish hatcheries and rearing stations, also referred to collectively as “fish culture stations” (https://www.maine.gov/ifw/fish-wildlife/hatcheries/index.html). This program is a “biological maintenance program to supplement natural reproduction” of fish “where there isn’t a suitable spawning and nursery habitat, or when there’s an overwhelming presence of predator or competitor fish” (MDIFW).

[7] https://www.biomatrixwater.com/products-overview/

[8] Floating Island Improve Water Quality Lake: Stories of Progress in Achieving Healthy Waters (JULY 14, 2023) https://www.epa.gov/pa/floating-wetland-islands-help-restore-large-pa-lake

[9] https://inhabitat.com/living-machines-turning-wastewater-clean-with-plants/

[10] https://www.toddecological.com/projects

[11] https://www.climatefoundation.org/marine-permaculture.html

[12] Marine permaculture: Design principles for productive seascapes (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590332224000344)

[13] Ocean Permaculture with Brian von Herzen (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uB6mRC53SNE)