Are there enough minerals in the world for a total transition to an alternative energy system?

There’s an ongoing debate concerning the availability of minerals needed for a full transition to alternative energy sources. This conversation involves factors such as the Earth’s resource capacity, energy return on investment (EROI) for various energy technologies, technological advancements, and the practicality of shifting away from fossil fuels.

Many discussions have raised concerns about the adequacy of critical minerals required for renewable energy technologies like solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicle (EV) batteries. These technologies rely on materials such as rare earth elements, lithium, and cobalt, which might not be as abundant as more common resources. However, advancements in technology and improved recycling methods are being considered to address these concerns.

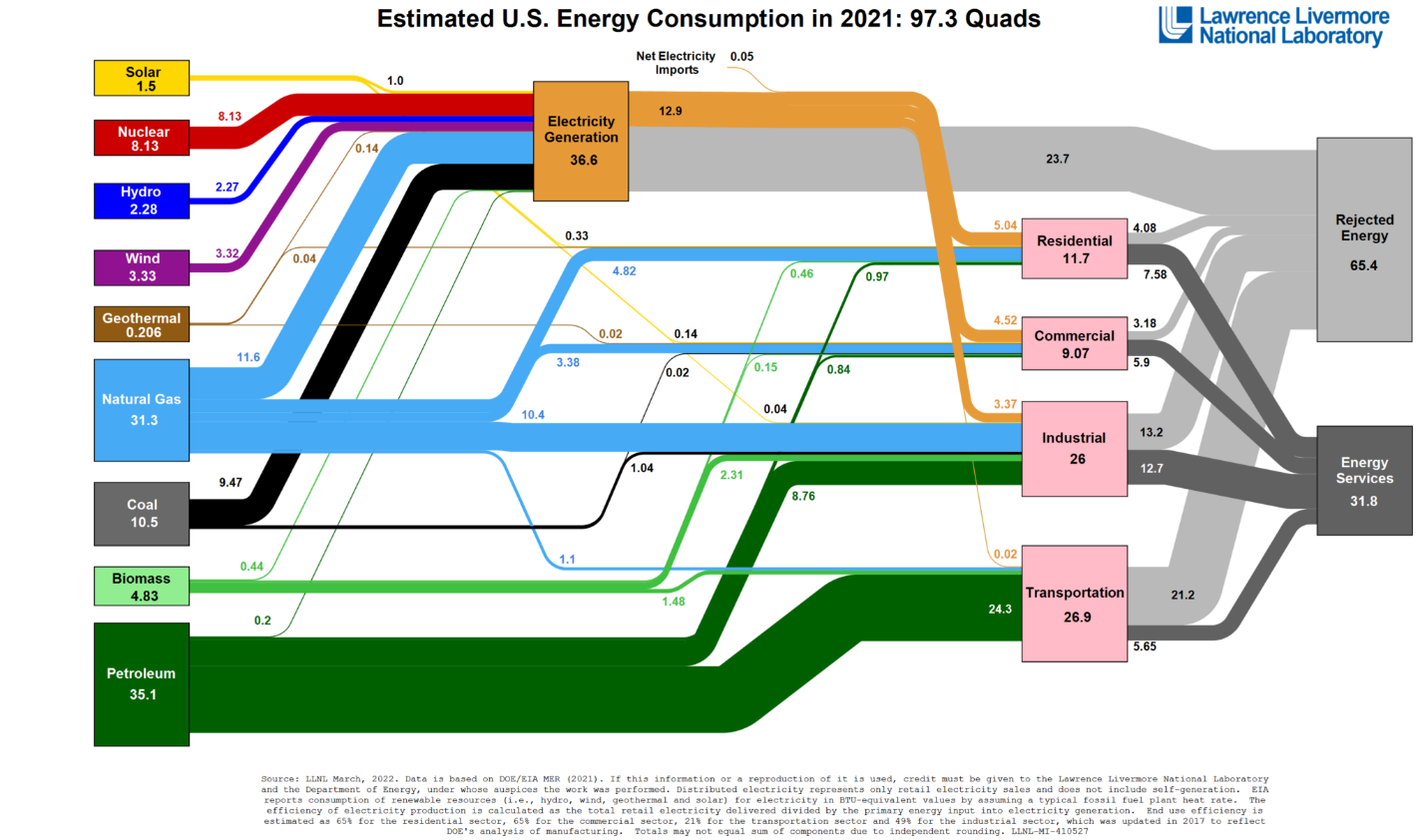

Recently, I have been reading about energy return on investment and energy flows in the current system (Brockway, 2019 and Barnard, 2023). Energy return on energy invested (EROI) is a calculation that experts use to try to answer questions about transitioning the energy system. EROI tells us the proportion of return on investment for producing energy and this can be then compared to the percentage that is used in the system and the investment needed to use it. Unfortunately, some methodologies for calculating EROI focus on the production side and compare energy source to source. These experts claim that since the EROI on oil is so much higher than for renewables, transition would be impossible from a sheer energy perspective. Other experts have begun to look at energy flows through the system, factoring wasted energy into the equation. These experts are saying that renewable energy produces such little waste that the EROI is comparable with oil after factoring in efficiency (Brockway, 2019). Still others are saying that as the cost of extracting and processing the finite resource rises the transition to renewables is inevitable (Barnard 2023).

Energy is often viewed as the economy is, as a supply and demand equation. After all, the economy is largely a story of energy inputs and outputs. On the supply side, people pay for energy produced and delivered with utilities accounts. This view is loaded with assumptions and hides energy waste out of view entirely. As a result, consumers pay for the lost 65% of energy generated in the delivery fees along with grid maintenance costs!With the supply side getting most of the attention we can easily stop imagining a brighter future with a thriving economy for our descendants.

However, the demand side of the equation is simply the wattage hours, rather than the cost of wattage hour. The wattage hours metered, the gallons pumped, or cordage dropped represents the demand side of the equation. A recent article by Micheal Barnard, for example, says that, “The primary energy fallacy is the assumption that all the energy, in all of the oil, gas and coal that we burn today must be replaced. We don’t need to replace it, we need to replace the unwasted energy services.” (Barnard, 2023). And that is less by a factor of two-thirds! Viewing it from this perspective suddenly seems much more doable.

The technologies are developing rapidly, for storage especially, but the intermittency of renewable energy is still a challenge to be met. The scale of that challenge, however, is less ominous than I thought. If we are building that new system for energy actually used and not comparing sources solely on the basis of production ROI, the future looks brighter. While concerns about mineral availability and EROI are well founded, ongoing developments suggest that a complete transition to an alternative energy system is plausible. This transition will likely require a combination of technological advancements, efficient energy utilization, and a shift in focus from energy replacement to maximizing energy services while reducing waste.

By Rachel Lyn Rumson

References

Barnard, M. (2023, February 13). Why Aren’t Energy Flows Diagrams Used More To Inform Decarbonization? CleanTechnica. https://cleantechnica.com/2023/02/13/why-arent-energy-flows-diagrams-used-more-to-inform-decarbonization/

SKAGEN Fondene (Director). (2023, January 16). Mark Mills: The energy transition delusion: inescapable mineral realities. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sgOEGKDVvsg

Brockway, P. E., Owen, A., Brand-Correa, L. I., & Hardt, L. (2019). Estimation of global final-stage energy-return-on-investment for fossil fuels with comparison to renewable energy sources. Nature Energy, 4(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0425-z