Biking has exploded in popularity in recent years around the world, both as a recreational pursuit and as a way to commute. What good does it provide society beyond being just a fun activity? This blog post by our summer 2023 intern, Maddie Nakashian, takes a deep dive in to how has biking impacted the United States and how the biking industry impacts the economy and the environment. Maddie attends high school in Northampton MA.

Biking in American History

Biking has been an integral part of American culture for centuries. Its rich history began with the creation of the “Ordinary”– the comical-looking bike with an enormous front wheel. Americans began importing bicycles from Europe, as safer modifications created the “Safety” model, which resembles the classic bicycle that we all know today. Its popularity surged in the 19th century, as the working class now had an affordable means of transportation, without the use of horses and carriages, which required far more maintenance.

Bikers were some of the first advocates for better road maintenance, which (quite literally) paved the way for a new and growing industry to take over – the automobile industry. Cars began replacing bikes, and by the 1940s and the introduction of highways, biking became essentially obsolete.

Decades passed like this, until the 1970s, when biking experienced a resurgence. With Veterans returning from Vietnam, Baby Boomers wanting to be “different” from older generations, and the environmentalist movement gaining traction, biking began gaining popularity again. But it was fleeting: Environmentalist and former Secretary of State Stewart Udall predicted it best: “…people will cling to their cars because there is no alternative”. For nearly half a century, this remained true.

Biking Today

The decline in biking has been reversed in recent years, with the pandemic helping create yet another biking boom. Closed gyms and social distancing inspired many to take on biking as a safely distanced and healthy activity that can easily be done with others. Even if it appears we are moving towards a more sustainably bike-centered world, the boom will only last so long; we are just beginning to enter the bust. People are returning to their cars as their main mode of transportation, and renewing their gyms memberships.

Environmental Benefits from Biking

While we return to our car-dominated and dependent society, much of the world is yet to understand the benefits of biking and its crucial part in the economy and saving the environment, and just how much it can change the course of our future.

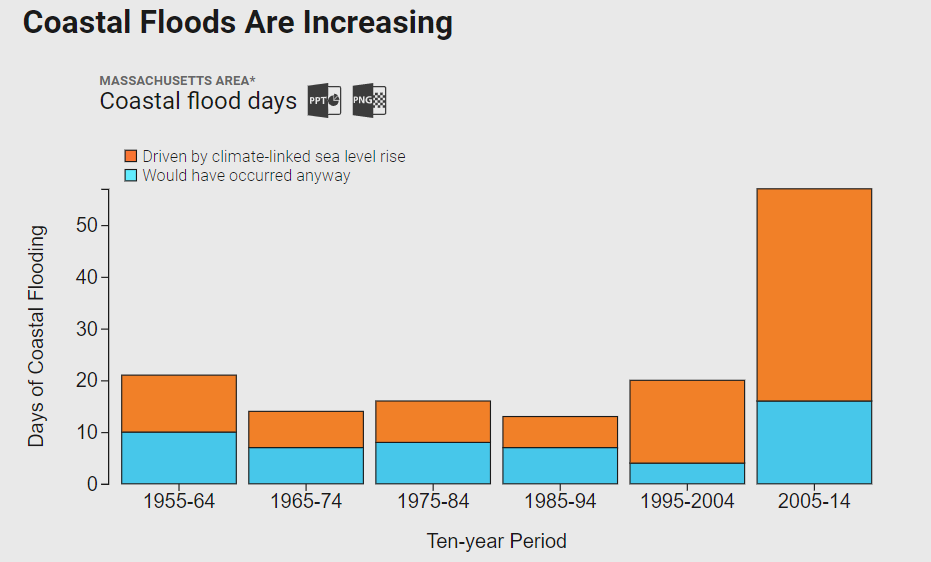

One of the first benefits that people associate with biking is being environmentally friendly. While this is widely appreciated by most, many people do not realize the extent to which biking helps keep our world a greener place. Increasing biking trips over using cars will be crucial to reverse and mitigate the drastic effects of climate change. This is emphasized by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which states that worldwide changes in how we travel is imperative to become a more eco-friendly world.

To start, let’s compare bikes to their counterpart, the car. One obvious fact about bikes is that they don’t emit CO2 or other greenhouse gas emissions, nor do they require fuel. Therefore, using bikes not only limits carbon emissions, but also preserves fuel and prevents it from being depleted so fast.

However, many underestimate just how big an impact biking can have on depleting carbon emissions and saving fuel. A modest increase in biking worldwide could save between 6 -14 million tons of CO2 from being emitted every year (How Riding a Bike Benefits the Environment | UCLA Transportation). In a world where we are rapidly and exponentially increasing how much CO2 we emit, even small changes can make all the difference in our quickly warming world.

Additionally, car emissions are emitted at street level, which makes them arguably more dangerous than other emissions due to their proximity to humans. Therefore, reducing car emissions can have a direct impact on human’s health and safety – and one great way of doing that is choosing to bike instead! Furthermore, this same modest increase in biking also has the benefit of saving 700 million to 1.6 billion gallons of fuel (Environmental Impact | U.S. Bicycle Route System | Adventure Cycling Association). This is a major step in preserving what natural resources we have left.

However, there are other large differences in the composition of cars versus bikes, which have major implications on the environment. Cars contain many other types of harmful chemicals, such as antifreeze, VOC’s (volatile organic compounds), heavy metals, ozone, and many more. These chemicals can be deposited on soil and surface waters, which has plenty of adverse effects on ecosystems; by accumulating in ecosystems, these toxic chemicals can easily enter the food chain and worsen the quality of the food we eat.

Obviously, bikes don’t use any of these toxins and chemicals and thus there’s no worry of depositing them into the environment. However, there are other ways to gauge the eco-friendliness of bikes.

Using a bike over a car reduces car congestion — which occurs when cars sit idly while still being in drive — and noise pollution, which can have major impacts on nearby ecosystems and human health.

Another parameter that bikes can be valued is in their infrastructure and their impact on the environment. Bike paths are significantly smaller than roads, especially highways, use less resources and are also better for the environment than roads, which often cause water run-off and subsequent ground/water pollution.

Despite all this evidence, some people contend that there are practical reasons not to bike – certain commutes are just too long and burdensome to travel via bike, right? Well, according to one survey (National Household Travel Survey –League of American Bicyclists (bikeleague.org) more than half of all daily trips are sub three miles, which is the perfect distance for a bike ride! Overall, using bikes is far more eco-friendly on many fronts, and also more practical than many give them credit for.

Economic Benefits from Biking

Bikes obviously have a lot of environmental benefits. But, often overlooked are the economic benefits brought to both an individual and their local/national economy. During the pandemic, the industry experienced a boom like never before, and many used biking as a way to escape the inevitable reclusive lifestyle Covid brought to us all. However, with the pandemic coming to an end, biking popularity is fizzling out. Though, despite some bumps in the road, the industry is now starting to see the light of day and make a healthy recovery back into the market.

The global biking market was valued at nearly 110 billion dollars in 2022, and expected to nearly double its worth by 2030. However, just a market evaluation alone doesn’t show the economic benefits biking can bring. Not only is biking more cost-friendly for the user, but also has massive economic benefits for all of society. To start, biking costs far less for individuals than cars do for myriad reasons. They cost less to manufacture, purchase, and maintain relative to cars. To put it into perspective, purchase, operations and maintenance, fuel, and insurance costs for a bicycle approximately $3.00 per 100km traveled; a private car is six times more expensive, at approximately $18.00 per 100km (itdp.org). Other necessary but expensive commodities for cars, such as gas and parking, are not needed for biking.

Another major benefit of biking is it keeps you healthy, which, too, has an economic benefit for individuals and society. Being healthier leads to reduced medical bill costs and premature deaths. In Patna, India, a 15 percent increase in trips made by bicycle would reduce premature mortality by 755 lives per year, and save the city $166 million (Making the Economic Case for Cycling, ITDP).

While many could easily figure out how biking is less costly on an individual level, less understood are the economic benefits biking brings on a macro scale. First, biking infrastructure (including bike paths and lanes) can be built quickly and at a lower cost, while employing over four times more employees than it takes to construct a road (itdp.org)! Bike lanes slow down traffic, which allows people to better see storefronts, which could translate to more business: A 2009 study concluded that bikers, on average, spend more money and bring more business in certain areas than those driving vehicles.

Furthermore, making towns more bike friendly creates more jobs in the national industry, including delivery services, bike tourism jobs, manufacturing and maintenance of bikes, micro mobility services such as Citibike, and countless others. One study conducted by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy even found that every kilometer cycled generates $0.18 for society, whereas every kilometer driven costs society $0.16.

Certain sectors that utilize cycling more see significant benefits. The delivery sector is a great example: using bikes/E-bikes is more cost effective than using big trucks. One study even found that a dramatic increase in bicycling could save society upwards of 24 trillion dollars collectively, between 2015-2050 (Making the Economic Case for Cycling, ITDP). So overall, biking doesn’t just reduce costs for the individual, but has massive economic benefits – in both saving money and generating revenue – for all of society.

Much of this post has been studying biking and its relation to the economy and the environment. However, something particularly interesting is biking and its crossover of the two. One business which achieves this is the Pedal People, based in downtown Northampton, MA. As the name suggests, they offer myriad different transportation services, notably trash, compost, and recycling pickup, but are often hired to transport other goods as well. This business not only perfectly shows how biking can help the environment, but also how it can add to the economy and provide community service. Expansion has been slow, as the business is trying to open a new chapter in Easthampton, MA, and some associates are even hoping to create a similar business in Norway, Maine, but nonetheless, this bike-powered business has seen steady growth, and in years to come, become a more common model around the state, region, and country.